Cette question revient très fréquemment sur le tapis, et comme toujours, ma réponse fut sans nuance:

Puis j’ai réfléchi, et je suis allé voir les recommandations en vigueur.

Il en existe deux:

L’américaine est la moins directive sur l’utilisation des HBPM:

9.2.5. Bridging Therapy in Patients With Mechanical Valves Who Require Interruption of Warfarin Therapy for Noncardiac Surgery, Invasive Procedures, or Dental Care

Class I

1. In patients at low risk of thrombosis, defined as those with a bileaflet mechanical AVR with no risk factors,* it is recommended that warfarin be stopped 48 to 72 h before the procedure (so the INR falls to less than

1.5) and restarted within 24 h after the procedure. Heparin is usually unnecessary. (Level of Evidence: B)

2. In patients at high risk of thrombosis, defined as those with any mechanical MV replacement or a mechanical AVR with any risk factor, therapeutic doses of intravenous UFH should be started when the INR falls below 2.0 (typically 48 h before surgery), stopped 4 to 6 h before the procedure, restarted as early after surgery as bleeding stability allows, and continued until the INR is again therapeutic with warfarin therapy. (Level of Evidence: B)

Class IIa

It is reasonable to give fresh frozen plasma to patients with mechanical valves who require interruption of warfarin therapy for emergency noncardiac surgery, invasive procedures, or dental care. Fresh frozen plasma is preferable to high-dose vitamin K1. (Level of Evidence: B)

Class IIb

In patients at high risk of thrombosis (see above), therapeutic doses of subcutaneous UFH (15 000 U every 12 h) or LMWH (100 U per kg every 12 h) may be considered during the period of a subtherapeutic INR. (Level of Evidence: B)

Class III

In patients with mechanical valves who require interruption of warfarin therapy for noncardiac surgery, invasive procedures, or dental care, high-dose vitamin K1 should not be given routinely, because this may create a hypercoagulable condition. (Level of Evidence: B)

*Risk factors: atrial fibrillation, previous thromboembolism, LV dysfunction, hypercoagulable conditions, older-generation thrombogenic valves, mechanical tricuspid valves, or more than 1 mechanical valve.

[…]

LMWH is attractive because it is more easily used outside the hospital. One study of bridging therapy for interruption of warfarin included 215 patients with mechanical valves. In the total group of 650 patients, the risk of thromboembolism (including possible events) was 0.62%, with 95% confidence intervals of 0.17% to 1.57%. Major bleeding occurred in 0.95% (0.34% to 2.00%). However, concerns about the use of LMWH for mechanical valves persists, and package inserts continue to list a warning for this use of these medications.

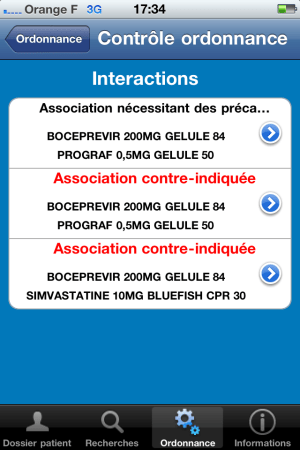

En fait, elle ne recommande rien sur ce point précis. Le praticien qui prescrit des HBPM le fait à ses risques et périls.

L’européenne est nettement plus précise:

Interruption of anticoagulant therapy

Although most instances of short-term anticoagulation interruption do not lead to thrombo-embolism or valve thrombosis, the corollary is that most cases of valve thrombosis occur following a period of anticoagulation interruption for bleeding or another operative procedure.

Anticoagulation management during subsequent non-cardiac surgery therefore requires very careful management on the basis of risk assessment. Besides prosthesis- and patient-related prothrombotic factors (Table 17), surgery for malignant disease or an infective process carries a particular risk, due to the hypercoagulability associated with these conditions. For very high-risk patients, anticoagulation interruption should be avoided if at all possible. Many minor surgical procedures (including dental extraction) and those where bleeding is easily controlled do not require anticoagulation interruption. The INR should be lowered to a target of 2.0.(Recommendation class I, Level of evidence B).

For major surgical procedures, in which anticoagulant interruption is considered essential (INR ,1.5), patients should be admitted to hospital in advance and transferred to intravenous unfractionated heparin (Recommendation class IIa, Level of evidence C). Heparin is stopped 6 h before surgery and resumed 6–12 h after. Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) can be given subcutaneously as an alternative preoperative preparation for surgery (Recommendation class IIb, Level of evidence C).

However, despite their wide use and the positive results of observational studies, the safety of LMWHs in this situation has not been widely established and their efficacy has not been proved by controlled studies, particularly in patients at high risk of valve thrombosis. When LMWHs are used, they should be administered twice a day, using therapeutic rather than prophylactic doses, adapted to body weight and if possible according to monitoring of anti-Xa activity. LMWHs are contraindicated in case of renal failure.

Despite the low level of evidence for both strategies, the committee favours the use of unfractionated intravenous heparin.

Donc les HBPM sont une alternative malgré l’absence d’argument d’essai contrôlé. Les auteurs recommandent néanmoins l’héparine non fractionnée.

Voilà voilà voilà…

Donc, les HBPM, c’est possible mais sans preuve scientifique bien nette.

Donc mea culpa, les recos en parlent et ne les excluent pas formellement.

Mais pour moi, étant donné la faiblesse des preuves scientifiques en faveur de leur utilisation, ça reste non.

Un peu hors sujet, mais intéressant quand même, les recommandations de l’ACCP de février 2012 parlent des HBPM chez les porteurs de valves mécaniques en post-opératoire immédiat de chirurgie cardiaque:

9.1 Early Postoperative Bridging to Intermediate/ Long-term Therapy (Postoperative Day 0 to 5)

9.1. In patients with mechanical heart valves, we suggest bridging with unfractionated heparin (UFH, prophylactic dose) or LMWH (prophylactic or therapeutic dose) over IV therapeutic UFH until stable on VKA therapy (Grade 2C)

Mais cette période reste très particulière et ne doit certainement pas être généralisée. La suite de cette note ici.

43.297612

5.381042

Pour partager cette note: